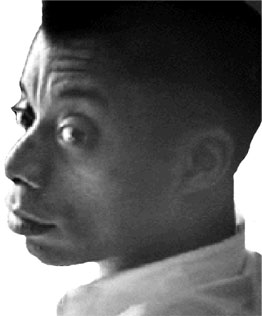

| Emmett Till knew segregation. McCosh Elementary was a public school with

black students only. When Mamie Bradley, (now the late Mamie Till Mobley)

Emmett’s mother, made plans to send him south for the summer on the Illinois

Central, she knew he would have to ride in the train’s colored section. But the

segregation, discrimination and racism Emmett knew in the North was nothing like

the segregation, discrimination and racism he rode into in Mississippi. His only

warning came from his mother, a Mississippi native who had left for Chicago with

her family when she was two years old. She told her boy not to fool with white

people down south. "If you have to get on your knees and bow when a white person

goes past, do it willingly." His cousin, Curtis Jones, recalled that Emmett liked to pull pranks. One

Wednesday evening in August, 1955, Emmett and Curtis drove Mose Wright’s ’41

Ford to Bryant’s Grocery and Meat Market, a country store with a big metal

Coca-Cola sign outside.

There the boys met up with some other black children, and Curtis Jones began

a game of checkers with a seventy-year-old black man sitting by the side of the

building. Outside the store, Emmett was showing off a picture of a white girl

who was a friend of his in Chicago. Till bragged to the titillated boys that

this white girl was his girl, and Jones recalls that one of the southern boys

said, "Hey, there’s a white girl in that store there. I bet you won’t go in

there and talk to her." So he went in there to get some candy. When he was

leaving the store, he told her, "Bye, Baby." And that’s when the old man that

was playing checkers started telling us that she would go to her car, get a

pistol, and blow Emmett’s brains out."

The boys jumped in their car as Carolyn Bryant came out the swinging screen

doors. They sped out of the little town.

By the next day the incident had become just a good story to the two northern

boys. But the tale went beyond those in the car. One girl who had heard it

through the grapevine warned, "When that lady’s husband come back there is going

to be trouble. "Roy Bryant was out of town at the time, trucking shrimp from

Louisiana to Texas.

The boys kept the encounter a secret from Mose Wright, hoping it would blow

over. Three days passed, and the boys forgot about Emmett’s "Bye, Baby" to the

pretty white woman. But after midnight on Saturday, a car pulled off the gravel

road and headed through the cotton field to Mose Wright’s unpainted cabin. Roy

Bryant was back from his trucking job. He and his brother-in-law J. W. Milam had

come to Mose Wright’s cabin to get that "boy who done the talkin’," Mose Wright

told the men that the bow was from "up nawth" and didn’t know a thing about how

to act with white folks down south. He told them that the bow was only fourteen

that this was only his second visit to Mississippi. Why not give the boy a good

whipping and leave it at that? As the men dragged Emmett outside, one of them

asked Mose Wright, "How old are you, preacher?" "Sixty-four."

"If you cause any trouble, you’ll never live to be sixty-five," said the man.

They pushed Emmett into the back seat of the car and drove away.

Precisely what happened next is unknown. Two months after the trial, however,

William Bradford Huie, a white Alabama journalist, paid Milam and Bryant $4,000

to tell their story. The two Mississippians attempted to justify the murder by

claiming that they didn’t intend to kill Till when they picked him up at Mose

Wright’s house, that they had only wanted to scare him. But when the young boy

refused to repent or beg for mercy, they said, they had to kill him.

"What else could we do?" Milam told Huie. "He was hopeless. I’m no bully; I

never hurt a nigger in my life. I like niggers in their place. I know how to

work ‘em. But I just decided it was time a few people got put on notice."

Milam drove Emmett to the Tallahatchie River, Huie wrote, and made the boy

carry a seventy-five-pound cotton-gin fan from the back of the truck to the river

bank before ordering him to strip. Milam then shot the boy in the head.

The Milam and Bryant account of the incident left several questions

unanswered. One witness, for example, reported seeing Till and the two accused

with a group of other men, both black and white, before the murder. Who were

they? How and why would Milam and Bryant coerce blacks into helping them? Why

would they need other whites along if they had only wanted to intimidate the

boy? And, would a tongue-tied fourteen-year-old boy really make baiting

comments, as Milam and Bryant allege, to the men who were viciously beating him?

What we do know is that Mose Wright heeded the kidnappers’ order. He did not

call the police. But the next morning, Curtis Jones went to the plantation

owner’s house and asked to use the phone. He told the sheriff Emmett Till was

gone.

Till’s body was found three days later. The barbed wire holding the cotton-gin

fan around his neck had become snagged on a tangled river root. There was a

bullet in the boy’s skull, one eye was gouged out, and his forehead was crushed

on one side.

Milam and Bryant had been charged with kidnapping before the gruesome corpse

was discovered. They were now charged with murder. The speed of the indictment

surprised many. But white Mississippi officials and newspapers said that all

"decent" people were outraged at what had happened and that justice would be

done. Milam and Bryant could not find a local white lawyer to take their case.

The Mississippi establishment seemed to be turning its back on them.

Meanwhile, the tortured, distended body pulled from the river became the

focus of attention. It was so badly mangled that Moses Wright could identify the

boy only by an initialed ring. The sheriff wanted to bury the decomposing body

quickly. But Curtis Jones called Chicago, passing word to Till’s mother first of

Emmett’s death and then of the imminent burial. She demanded that the corpse be

sent back to Chicago. The sheriff’s office reluctantly agreed, but had the

mortician sign an order that the casket was not to be opened.

As soon as the casket arrived in Chicago, however, Mrs. Bradley did open it.

She had to be sure, she said, that it was really her son, that he was not still

alive and hiding in Mississippi. She studied the hairline, the teeth, and in

vengeance declared that the world must see what had been done to her only child.

There would be an open-casket funeral.

The thirty-three-year-old mother collapsed to the concrete train platform

crying, "Lord, take my soul." She had to be taken from the station in a

wheelchair.

"Have you ever sent a loved son on vacation and had him returned to you in a

pine box, so horribly battered and water-logged that someone needs to tell you

this sickening sight is your son – lynched?" Mamie Bradley (Mamie Till Mobley)

asked reporters afterwards.

Emmett Till’s horribly battered, water-logged corpse would shock and disgust

the city of Chicago, and after a picture of it was published in the black weekly

magazine, Jet, all of Black America saw the mutilated corpse.

On the first day that the casket was open for viewing, thousands and

thousands of people lined the streets outside the Rainer Funeral Home. The

funeral was held on Saturday September 3, 1955, two thousand (2000) people gathered outside the

church on State Street. Mamie Bradley (Mamie Till Mobley) delayed burial for

four days to let "the world see what they did to my boy."

It is difficult to measure just how profound an effected the public viewing

of Till’s body created. But without question it moved black America in a way the

Supreme Court ruling on school desegregation could not match. Contributions to

the NAACP’s "Fight Fund," the war chest to help victims of racial attacks,

reached record levels. Only weeks before, the NAACP had been begging for support

to pay its debts in the aftermath of its Supreme court triumph.

The Cleveland Call and Post, a Black newspaper, polled the nation’s major

Black radio preachers and found five of every six preaching on the Till case.

Half of them were demanding that "something be done in Mississippi now,"

according to the paper.

White Mississippians responded differently as the case became a national

cause. As northerners denounced the barbarity of segregation in Mississippi, the

state’s white press angrily objected to the NAACP’s labeling of the killing as a

lynching. Jackson Clarion Ledger writer Tom Ethridge called the condemnation of

Mississippi a "Communist plot" to destroy southern society. Civil rights

activists were frequently accused of being Communists of Communist sympathizers.

Public opinion in Mississippi galvanized in reaction to the North’s scorn.

Five prominent Delta attorneys now agreed to represent Milam and Bryant. A

defense fund raised $10,000. Signs of support suddenly appeared from the same

local officials who had at first put distance between themselves and the men

charged with the boy’s brutal murder. The sheriff, declaring that the body was

too badly decomposed to be positively identified as Till’s did no investigative

work to help the prosecution prepare its case. A special prosecutor had to be

appointed by the state, but he was given no budget or personnel with which to

conduct a probe.

On September 19, 1955 less than two weeks after Emmett Till was buried in

Chicago, Milam and Bryant went on trial in a segregated courthouse in Sumner,

Mississippi. The press, particularly the black press, was in the courtroom.

Reporters from desegregation, this could make a good story—a telling example of

how the South was reacting to the changing status of Black people.

No one knew if any Black witnesses would dare testify against the white men.

Curtis Jones, who in later years became a Chicago Policeman, recalls that his

mother forbade him to return to Mississippi to testify at the trial of his

cousin’s accused murderers. "My mother was afraid something would happen to me

like something happened to Emmett Till."

Without a witness, there would be no case. But in 1955, for a black man to

accuse a white man of murder in Mississippi was to sign his own death warrant.

Violence had long been used in the South as a means of intimidating Black People

into passivity, but this murder was particularly brutal and all the more

threatening. White Mississippi, angry at the northern press’ interest in the

case, was closing ranks. The word spread throughout the Black community: Keep

your mouth shut.

Mose Wright had not slept at his home since the kidnapping. He feared the men

might return. His wife, Elizabeth Wright, never went back to the cabin after

that night. "Tll Simmie (her son) to get any corset and one or two slips or a

dress or two and bring them to me," she wrote in a note to her husband from her

hiding place. After the indictment, Wright received anonymous warnings to leave

the state before the trial began. He was told to take his family and "get out of

town before they all get killed.

But Wright didn’t leave the state. Although he had been intimidated by the

kidnappers the night they took Emmett, he was now going to be a witness for the

prosecution. A Black man was going to testify.

Just before the trial began, Black reporters had gotten word that Wright

would be a witness. Twenty years earlier, in another Mississippi courthouse,

when a Black boy accused of raping a white woman got up to testify, a white man

in the courtroom pulled out a revolver and started shooting. Anticipating the

fury that Mose Wright’s testimony would prompt, the Black reporters made plans

for the moment, just in case the whites in the courtroom turned on the few

Blacks. James Hicks, a reporter covering the trial for the Amsterdam News,

described their plan this way. "We had worked it out where I was going to get

the gun (from a bailiff) seated in front of the Black reporters, somebody else

was going to take this girl (Cloyte Murdock Larsson, a reporter for Jet) to the

window, she was going to go out the window two floors down…. Then we were just

going to grab the chairs ….. and fight our way out – if we could."

|