aa

|

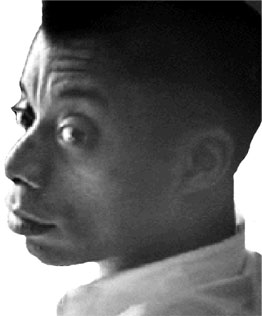

Marcus Garvey

The Man and the Movement

While Garvey's name has achieved legendary proportions, and his

movement has had an ongoing international impact, Garvey as a mortal being was a

man who embodied the contradictions of his age. He was seen by his own

contemporaries in a plethora of ways, both positive and negative. "A little

sawed-off and hammered down Black Man, with determination written all over his

face, and an engaging smile that caught you and compelled you to listen to his

story" was how the veteran black journalist John E. Bruce ("Bruce Grit")

recalled his initial encounter with the young Jamaican in the spring of 1916.

Encouraged by Booker T. Washington, Garvey had come to America hoping to gather

support for a proposed school, to be built in Jamaica, patterned on the model of

the famed Tuskegee Institute. By the time Garvey could get to the United States,

however, Washington was dead. Garvey started with a nucleus of thirteen in a

dingy Harlem lodge room. Within a few short years, he was catapulted to the

front rank of black leadership, at the head of a social movement unprecedented

in black history for its sheer size and scope. Writing in 1927, six months

before Garvey was to be deported from America, Kelly Miller, the

African-American educator and author, reflected upon the phenomenon:

Marcus Garvey came to the U.S. less than ten years ago,

unheralded, unfriended, without acquaintance, relationship, or means of

livelihood. This Jamaican immigrant was thirty years old, partially educated,

and 100 per cent black. He possessed neither comeliness of appearance nor

attractive physical personality. Judged by external appraisement, there was

nothing to distinguish him from thousands of West Indian black people who flock

to our seaport cities. And yet this ungainly youth by sheer indomitability of

will projected a propaganda and commanded a following, within the brief space of

a decade, which made the whole nation mark him and write his speeches in their

books.

In the world of the twenties, personalities quickly became

notable and were fastened upon by admirers, detractors, and the merely curious.

But even by the standards of the day, Garvey's rise from obscurity was

spectacular. Speaking to an audience at Colon, Panama, in 1921, Garvey himself

noted that "two years ago in New York nobody paid any attention to us. When I

used to speak, even the policeman on the beat never noticed me."

Garvey voiced the marvelous nature of his own rise when he asked

an audience in 1921 "how comes this New Negro? How comes this stunned

awakening?" The ground had been prepared for him by such outspoken voices as

those of Hubert H. Harrison, A. Philip Randolph, Chandler Owen, and

W. A. Domingo. These and other stepladder orators---who began speaking along

Lenox Avenue with the arrival of warm weather in 1916 and whose number rapidly

grew with each succeeding summer---were the persons who, along with Garvey,

converted the black community of Harlem into a parliament of the people during

the years of the Great War and after. The World War I era was the time of the

rise of "the ebony sages," as William H. Ferris termed the New Negro

intelligentsia, who laid the foundation in those years for what would eventually

come to be known as the Harlem Renaissance. Garveyism was fed in an environment

where "in barber shops and basements, tea shops and railroad flats," Ferris

revealed, "art and education, literature and the race question were discussed

with an abandon that was truly Bohemian." By the middle of the decade, Ferris

would go so far as to claim that "The New Negro is Garvey's own Child, whose

mother is the UNIA."

When the UNIA was organized in Harlem in February 1918, its

Jamaican leader merged not only with representatives of the New Negro, but with

another minority: from the perspective of America's polyglot of ethnic groups,

Garvey was simply one more immigrant voice. The Garvey phenomenon began amidst

the multiple migrations of America, and it was not unusual to find Garvey

issuing pronouncements of confraternity with the causes of various immigrant

groups.

"Just at that time," recalled Garvey, speaking in Liberty Hall

in early 1920 about his start as a street orator in Harlem, "other races were

engaged in seeing their cause through---the Jews through their Zionist movement

and the Irish through their Irish movement---and I decided that, cost what it

might, I would make this a favorable time to see the Negro's interest through."

A notable feature of Garveyism as a political phenomenon was the

staunch manner in which it accentuated the identity of interests among black

people all over the world. For Hodge Kirnon, this quality of internationalism

essentially defined the New Negro mood. He observed:

The Old Negro press was nationalistic to the extreme, even at

times manifesting antipathy and scorn for foreign born Negroes. One widely

circulated paper went as far as to cast sarcasm and slur upon the dress,

dialect, etc., of the West Indian Negro, and even advised their migration and

deportation back to their native lands-a people who are in every way law

abiding, thrifty and industrious. The new publications have eliminated all of

this narrow national sentimental stupidity. They have advanced above this. They

have recognized the oneness of interests and the kindredship between all Negro

peoples the world over.

A special feature by Michael Gold in the 22 August 1920 Sunday

supplement of the New York World reported upon Garvey's meteoric ascent, and

registered as well his immigrant status and the international nature of his

message. The headlines accompanying the story made the following announcement:

The Moses of the Negro Race Has Come to New York and Heads a

Universal Organization Already Numbering 2,000,000 Which is About to Elect a

High Potentate and Dreams of Reviving the Glories of Ancient Ethiopia

Gold captured a defining characteristic of the Garvey

phenomenon, namely, its rapid spread throughout the world, including sub-Saharan

and southern Africa. Writing from Johannesburg, South Africa, a number of years

later, Enock Mazilinko echoed the messianic vision of Garvey held by many in

America when he wrote that "after all is said and done, Africans have the same

confidence in Marcus Garvey which the Israelites had in Moses."

"Marcus Garvey is now admitted as a great African leader"

concurred James Stehazu, a Cape Town Garveyite; indeed, Garvey was the

embodiment for tens of thousands of black South Africans in the postwar years of

the myth of an African-American liberator.

"Already his name is legend, from Harlem to Zanzibar," allowed

the venerable Guardian of Boston when it appraised the significance of Garvey's

life in 1940.

But not everyone shared this concept of Garvey. Detractors

labeled him a madman or the greatest confidence man of the age. "We may

seriously ask, is not Marcus Garvey a paranoiac?" enquired the NAACP's Robert

Bagnall in his 1923 article "The Madness of Marcus Garvey." An earlier

psychological assessment by W. E. B. Du Bois diagnosed Garvey as suffering from

"very serious defects of temperament and training," and described him as

"dictatorial, domineering, inordinately vain and very suspicious." In the view

of the organ of South Africa's African Political Organization, "the

newly-created position of Provisional President of Africa [was] an empty honor

which no man in the history of the world has ever held, and no sane man is

likely to aspire after."

It was mainly as an embarrassment to his race, however, that

Garvey was dismissed. '"The Garvey Movement," reported Kelly Miller in 1927,

"seemed to be absurd, grotesque, and bizarre."

"If Gilbert and Sullivan were still collaborating," commented

one African editorial writer, "what a splendid theme for a musical comic opera

Garvey's pipe-dream would be." W. E. B. Du Bois echoed this opinion when he

described UNIA pageantry as like a "dress-rehearsal of a new comic opera. A West

Indian resident in Panama, writing in the April 1920 issue of the Crusader,

offered an ironic commentary on what he took to have been Garvey's assumption of

the grand title of African potentate: "Pardon me," the gentleman interposed,

"but this sounds like the story of "The Count of Monte Cristo' or the 'dream of

Labaudy,' or worse still, 'Carnival,' as obtains in the city of Panama, where

annually they elect 'Her Gracious Majesty, Queen of the Carnival,' and other

high officials."

White commentators were not excluded from this game of

describing Garvey's conduct through the metaphor of entertainment. Borrowing

from Eugene O'Neill's surrealistic play about the dramatic downfall of a

self-styled black leader, Robert Morse Lovett referred to Garvey as "an Emperor

Jones of Finance" to convey Garvey's financial ineptitude to highbrow readers of

the New Republic.

The wide variety of contemporary opinion about Garvey serves as

a backdrop for his own eclectic descriptions of himself. He once announced that:

"My garb is Scotch, my name is Irish, my blood is African, and my training is

half American and half English, and I think that with that tradition I can take

care of myself."

While Garvey told his audiences that his mind was "a complete

machine," one "that thinks absolutely in the original," and, on another

occasion, that his mind was "purely Negro," he also lamented that "the average

Negro doesn't know much about the thought of the serious white man."

His own ideology encompassed these two contradictory

conceptions. For him, the thought of the New Negro had to be a new thought, for

it was incumbent upon the race to develop intellectual (as well as economic and

political) independence as a precondition of survival in a world ruled by

Darwinian ideas of the survival of the fittest. Nevertheless, the New Negro had

to build this original thought on a strong foundation in the mainstream

intellectual tradition, borrowing from that tradition while creating new racial

imperatives. The present collection is a testimony to the diverse origins of

Garvey's thought and to the ways in which he consciously embraced many of the

dominant intellectual traditions of his age, reshaping them to the cause of

pan-African regeneration.

|

|

a |