aa

|

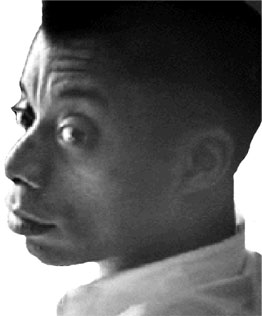

Marcus Garvey

Anti-Semitism

Yet even while Garvey supported Jews as positive socioeconomic

and political role models, he was by no means free from the anti-Semitism of his

time. He became increasingly anti-Semitic in his rhetoric following conviction

on mail-fraud charges in 1923, when he became convinced that Jewish and Catholic

jurors and Judge Julian Mack, a leading Zionist and former head of the Zionist

Organization of America, had been biased in the hearing of the case because of

their political objections to his meeting with the acting imperial wizard of the

Ku Klux Klan---an avowedly anti-Semitic and anti-Catholic organization---in

1922. "When they wanted to get me," Garvey informed the African-American

journalist Joel A. Rogers in 1928, "they had a Jewish judge try me, and a Jewish

prosecutor. I would have been freed but two Jews on the jury held out against me

ten hours and succeeded in convicting me, whereupon the Jewish judge gave me the

maximum penalty."

This bitterness continued to pervade his thinking, and tainted

the positive view of Jews he upheld earlier in his career. By the mid-1930s,

racist suspicion of the motivation of Jews was mixed with a more positive

identification with Jews as an oppressed minority, so that Garvey frequently

made statements about Jewish solidarity that were contradictory.

Garvey was a propagator of the anti-Semitic rhetoric common in

the political era epitomized by the formation of the Rome-Berlin Axis in October

1936. He identified with the rise of both Hitler and Mussolini from lower-class

status, and admired the power manifested in their nationalistic brand of

leadership. He praised both men in the early thirties as self-made leaders who

had restored their nations' pride, and used the resurgence of Italy and Germany

as an example to black people for the possible regeneration of Africa. He

admired in particular the remarkable ideological stamp the fascist leaders had

succeeded in imprinting on the world. "In politics as in everything else," he

declared, "movements of any kind [once] established, when centralized by leading

characters generally leave their impression, and so Hitler, Mussolini, Stalin

and the Japanese political leaders are leaving on humanity at large an indelible

mark of their political disposition."

This admiration was tinged with jealousy over the spectacular

impact of the fascist movement. In 1937 he went so far as to claim in a London

interview with Joel A. Rogers that, as Rogers reported, . . . his Fascism

preceded that of Mussolini and Hitler. "We were the first Fascists," [Garvey]

said, "when we had 100,000 disciplined men, and were training children,

Mussolini was still an unknown. Mussolini copied our Fascism."

Later the same year he declared that the "UNIA was before

Mussolini and Hitler ever were heard of. Mussolini and Hitler copied the

program of the UNIA---aggressive nationalism for the black man in Africa."

His naive identification with fascism in the mid-thirties merged

readily with the unfortunate anti-Semitic beliefs he had been voicing since the

mid-twenties. In his lessons for the School of African Philosophy---which were

first delivered when the events of the past few years had brought Nazi policies

of racial discrimination and oppression to the attention of the world---Garvey

cautioned against relying on Jews, stating that the very racial solidarity he

admired made Jews loyal only to themselves and not to other racial groups. These

distasteful comments mark the development of anti-Semitism within the black

community in the United States, reflecting the tension that had developed in

urban areas, in the course of the previous twenty years, between black people

who had migrated from the South or the Caribbean in the World War I era and

Jewish immigrants already established in the cities. Black perceptions of Jews

were influenced by personal resentment of Jewish landlords and shopkeepers, on

whom many black people depended for housing and consumer goods. Jews, in turn,

were influenced by the larger atmosphere of racial prejudice against black

people and prevailing patterns of residential segregation. This economic tension

and cultural dissonance between Jews and black people in areas where the UNIA

was strong made black people receptive toward anti-Semitic theories of

international financial conspiracy.

These racist theories, popular in the early twenties, were

propagated by such widely distributed organs as Henry Ford's Dearborn

Independent and The International Jew. Garvey admired Ford as a self-made

captain of industry, and was undoubtedly familiar with the anti-Semitic leanings

of the Ford publications. Garvey also subscribed to the notorious Protocols of

the Elders of Zion, which went through six editions in the United States between

1920 and 1922. He told Joel A. Rogers in the course of a 1928 interview in

England that "the Elders of Zion teach that a harm done by a Jew to a Gentile is

no harm at all, and the Negro is a Gentile."

Garvey apparently accepted the theory---widely popular in the

twenties and propagated by Ford's Dearborn Independent reporters and the

Protocols---about the existence of a Jewish-capitalist-Bolshevik conspiracy.

Garvey details the same conspiracy theory in his otherwise sympathetic

editorials criticizing Nazi persecution of Jews. "Hitler is only making a fool

of himself," Garvey argued in publicly denouncing Hitler's attacks upon Jews,

declaring further:

Sooner or later the Jews will destroy Germany as they destroyed

Russia. They did not so much destroy Russia from within as from without, and

Hitler is driving the Jews to a more perfect organization from without Germany.

Jewish finance is a powerful world factor. It can destroy men, organizations and

nations. When the Jewish capitalists get together they will strike back at

Germany and the fire of Communism will be lighted and Hitler and his gang will

disappear as they have disappeared in Russia . . . If Hitler will not act

sensibly then Germany must pay the price as Russia did.

Two years before, when Hitler rose to power in Germany, Garvey

wrote of the ability of the Jews to ruin Germany financially. "The Jews are a

powerful minority group," assayed Garvey, "and although they may be at a

disadvantage in Germany, they can so react upon things German as to make the

Germans, and particularly Hitler and the Nazis, rue the day they ever started

the persecution."

While Garvey promulgated prejudicial theories about Jewish

culture in the lessons from the School of African Philosophy and elsewhere, he

also expressed contrary views, at times harshly criticizing racial

discrimination against Jews. In 1933 he directly linked the Jewish reputation

for business acumen with German anti-Semitism. He strongly denounced

discrimination against Jews as a minority group and ascribed anti-Jewish

prejudice to racism motivated by jealousy of Jewish economic success. "The

Jewish race is a noble one," he wrote in a 28 March 1933 New Jamaican editorial,

and "the Jew is only persecuted because he has certain qualities of progress

that other people have not learnt." He then drew a direct analogy between the

persecution of Jews and the prejudice directed against black people in the

United States, and strongly denounced Nazi racial intolerance. He

specifically denounced Hitler's and Mussolini's designs on African colonies, and

linked Nazi prejudice against black people with the persecution of Jews,

describing both as racist policies that presented dangerous ramifications for

world affairs.

|

|

a |