aa

|

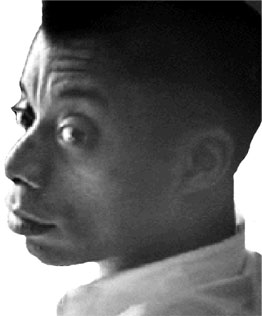

Marcus Garvey

Poetry and Oral Tradition

Garvey's penchant for literary allusion and persuasion reflects

his own belief that literature, particularly poetry, can be a powerful agent of

personal uplift and a tool for teaching success. In the first lesson of the

School of African Philosophy course for prospective UNIA leaders, he told his

students to "always select the best poets for your inspirational urge." Writing

a review of a poetry reading for the New Jamaican, he reminded his readers that

"many a man has gotten the inspiration of his career from Poetry."

He went on to describe the beneficial effects of poetry

readings, stating that the listener "is able to enter into the spirit of the

Poets who write the language of their souls," while the poets themselves, in

creating poetry, are forced to contemplate their lives deeply, "and when they

start to think poetic they may realize that after all life is not only an 'empty

dream.'" From this perspective, poetry grants those receptive to it inspiration,

and inspiration leads to ideation and action.

Garvey's writings and speeches also show the powerful legacy of

his schooling in Victorian moral exhortation through elocution, as well as his

genius in integrating the practice of declamation with West Indian and

African-American traditions of verbal performance. In the dialogues created for

the Black Man in the mid-1930s, Garvey adapted the Platonic form of didactic

conversation between teacher and student, with its progression of statement,

discussion, and debate, leading to the transfer and growth of knowledge. The

dialogues also demonstrate his special sensitivity to communicating with an

audience steeped in an oral tradition. By translating the written word into a

script of two voices that was to be read as if it were spoken, Garvey created a

kind of call-and-response conversational pattern designed both to uplift and to

instruct. In any event, Garvey loved an argument.

|

|

a |