aa

|

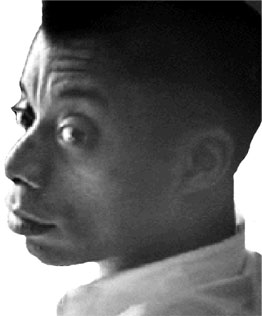

Marcus Garvey

The Doctrine of Success

Garvey's strong belief in the success ethic, a theme that forms

a constant thread throughout his speeches and writings, is reflective of the

popular culture of his time. Speaking in Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 1937, Garvey

summed up for his audience the principle that he claimed life had taught him:

"At my age I have learnt no better lesson than that which I am going to impart

to you to make a man what he ought to be---a success in life. There are two

classes of men in the world, those who succeed and those who do not succeed."

Rejecting the class analysis being embraced by some of his black contemporaries,

Garvey regularly illustrated his speeches with rags-to-riches stories, and

offered examples from the fields of business and industry to his followers as

models to emulate. In 1927 Joseph Lloyd, a Garveyite in Cuba, won a UNIA-sponsored

"Why I am a Garveyite" contest with an essay on his Garvey-inspired

aspirations to become a black captain of industry or political leader. Garvey

"has taught me," Lloyd wrote in the 6 January 1927 issue of the Negro World,

"that I can be a Rockefeller, a Carnegie, a Henry Ford, a Lloyd George, or a

Calvin Coolidge." Garvey himself had earlier asked readers of the Negro World in

a 6 November 1926 editorial, "Why should not Africa give to the world its black

Rockefeller, Carnegie, Schwab, and Henry Ford?" In the following year he spelled

out the connection between such economic achievement and political power,

informing his audience that

there is no force like success, and that is why the individual

makes all efforts to surround himself throughout life with the evidence of it.

As of the individual, so should it be of the race and nation. The glittering

success of Rockefeller makes him a power in the American nation; the success of

Henry Ford suggests him as an object of universal respect, but no one knows and

cares about the bum or hobo who is Rockefeller's or Ford's neighbor. So, also,

is the world attracted by the glittering success of races and nations, and pays

absolutely no attention to the bum or hobo race that lingers by the wayside.

Garvey's gospel of success was distinguished from more

traditional versions of the doctrine because he merged personal success with

racial uplift and established a link between these twin ideals and an

overarching vision of African regeneration. From Garvey's perspective, success

of the individual should serve the ends of the race, and vice versa. "There are

people who would not think of their success," Garvey insisted, "but for the

inspiration they receive from the UNIA." Speaking in New York in 1924, Garvey

claimed to have "already demonstrated our worth in helping others to climb the

ladder of success." Reciprocally, the UNIA relied for its own success on the

organized support of individuals. "Help a Real Race Movement: The Way to Success

Is Through Our Own Efforts" was the entreaty printed on the UNIA's contribution

card in the early 1920s.

Garvey offered a doctrine of collective self-help and racial

independence through competitive economic development. "As a race we want the

higher success that is within humanity's grasp," Garvey was quoted in the 21

February 1931 "Garvey's Weekly Digest" column of the Negro World: "We must

therefore reach out and get it. Don't expect others to pave the way for us

towards it with a pathway of roses, go at what we want with a will and then we

will be able to successfully out-do our rivals, because we will be expecting

none to help us." Garvey also told his followers that the achievement of a

higher class status among black people was the most direct route to obtaining

opportunities and individual rights. "Be not deceived," he wrote, in the spirit

of Andrew Carnegie, '"wealth is strength, wealth is power, wealth is influence,

wealth is justice, is liberty, is real human rights."

This imperative of success was tied to what a 21 March 1922

Negro World article termed "a universal business consciousness" among black

people in all parts of the world. By featuring the slogan "Africa, the Land of

Opportunity," emblazoned on a banner draped across a picture of the African

continent, the official stationery of Garvey's Black Star Line graphically

illustrated this philosophy of racial vindication and uplift through capital

investment and development.

|

|

a |