aa

|

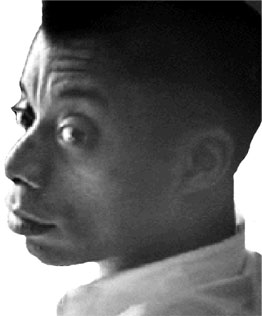

Marcus Garvey

The Ideal State and the UNIA

"Governing the Ideal State" emerges as an essay in

self-vindication and wish fulfillment and draws thinly disguised parallels

between Garvey's vision of the ideal state and his desires for the correct

operation of the UNIA. Just as the philosopher-ruler is the central theme of

Plato's Republic, so is Garvey the focus of the essay. Garvey's character might

also be adduced from the authoritarian type of society he proposes---an exercise

that would be consistent with Plato's attempt to sketch the four types of

character corresponding to the four types of society depicted in book 8 of the

Republic.

Written from prison, at a period in his life that called for

reflection about the course of his career and the factionalization and

corruption that had overtaken the movement, Garvey's essay takes on an

autobiographical quality, with significant psychohistorical connotations. Garvey

clearly identified with the extreme authoritarianism of the supreme leader who

appoints subordinate officials and exercises absolute authority over them. Just

as Garvey impeached or expelled UNIA officers who disagreed with his policies or

digressed from his vision of the organization's goals (often publicly disgracing

them in the process), so Garvey's Spartan utopia would ensure strict

accountability, as well as define the boundaries of conduct for subordinates.

The role of the president's wife as his personal accountant in the ideal state

closely parallels that of Amy Jacques Garvey as business manager at the UNIA

headquarters as well as overseer of her husband's---the president

general's---personal accounts.

Garvey suggests, through his philosophical musing on the

austerity of the ideal state, his own, as well as his wife's, exculpation by

sketching draconian consequences for fraud and mismanagement. At the same time,

Garvey's call for the disgrace of public officials who do not correctly perform

their duties reflects a desire for retribution and revenge against fellow UNIA

officers and staff members, many of whom he felt had deceived him and whom he

charged with graft. Similarly, the call for clemency toward a family member who

defied and reported corruption acknowledged Garvey's feelings toward those who

remained loyal to him and who had testified in his defense during the mail fraud

trial, offering evidence against the "disloyal" actions of others. The

recommendations that the president of the ideal state be freed from pecuniary

obligations are natural wishes from a man whose struggles to gain world renown

as the head of a movement were always compromised by debt and material need. In

addition, Garvey's description of the absolute leader as a man without friends

is also a poignant reflection of his own, perhaps deliberate, isolation from

close companionship, a theme that reappears in his advice to prospective UNIA

leaders in his lessons for the School of African Philosophy.

|

|

a |