aa

|

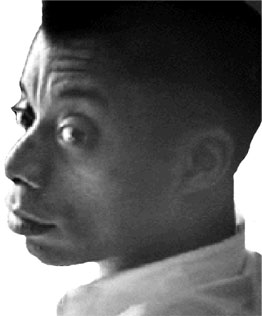

Marcus Garvey

Classical Influences and the Ideal State

Much of Garvey's theory of education---with its emphasis on

self-mastery and self-culture as precursors to good race leadership---can be

traced to the classical model of education, where the training of the child is

the basis of virtue, and virtue in turn is the necessary requirement of

statesmanship. "Governing the Ideal State," written by Garvey in Atlanta Federal

Penitentiary in 1925, manifests the influence of classical philosophy on

Garvey's thought and on his view of contemporary political events. The essay

stands also as a propagandistic exercise in self-vindication in the wake of

Garvey's recent conviction on fraud charges. It offers an indictment of the

behavior of UNIA leaders and staff members whose misconduct Garvey felt had led

to his imprisonment. It is also a scathing comment on the American political

system at large and on the widespread corruption among government officials and

leaders in the era of the Teapot Dome scandal.

Garvey enjoyed using classical allusions to convey to his

audiences the concept of greatness and nobility. In his 1914 pamphlet A Talk

with Afro-West Indians, he urged his readers to "arise, take on the toga of race

pride, and throw off the brand of ignominy which has kept you back for so many

centuries." Nearly two decades later he told readers that "the mind of Cicero"

was not "purely Roman, neither were the minds of Socrates and Plato purely

Greek." He went on to characterize these classical figures as members of an

elite company of noble characters, "the Empire of whose minds extended around

the world." The title of his 1927 Poetic Meditations of Marcus Garvey

parallels the title of the work of the "philosopher-emperor" of Rome, The

Meditations of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (121--180). Like the work

of Marcus Aurelius, Garvey's meditations included a fascination with the themes

of conduct and the moral tenets of Stoicism and Platonism.

In fact, Garvey subsequently described his "Governing the Ideal

State" as an abstract exercise to be likened to "Plato's Republic and

Utopia." And like Plato and the Greeks, Garvey shared a strong belief, though

he applied it to Africa of antiquity, in the notion of historical decline from a

golden age. Garvey believed civilizations were subject to an inevitable cyclical

process of degeneration and regeneration. In one of his earliest essays,

entitled "The British West Indies in the Mirror of Civilization" published in

the October 1913 issue of the African Times and Orient Review, he held up the

prospect of a future historical role for West Indian black people in relation to

Africa on the premise of this cyclical view. "I would point my critical friends

to history and its lessons," he advised, then proceeded to draw what was to be

one of his favorite historical parallels: "Would Caesar have believed that the

country he was invading in 55 B.C. would be the seat of the greatest Empire of

the World? Had it been suggested to him would he not have laughed at it as a

huge joke? Yet it has come true." The essay is important as an early example

of the equation, in Garvey's mind, of history with empire building and decline.

In "Governing the Ideal State," he announced the failure of

modern systems of government and called for a return to the concept of the

archaic state, ruled over by an "absolute authority," or what Aristotle termed

an absolute kingship. The fact that Garvey was well versed in Aristotle is

highlighted by his request to his wife, shortly after the beginning of his

imprisonment, to send him a copy of A. E. Taylor's Aristotle (1919), a standard

commentary. In his essay, Garvey rejected democracy in favor of a system of

monarchy or oligarchy similar to the one presented in Aristotle's Politics, the

rule of "one best man," along with an administrative aristocracy of virtuous

citizens. As was the case in Aristotle's utopia-where those individuals with a

disproportionate number of friends would be ostracized from society, while an

individual demonstrating disproportionate virtue should be embraced and given

supreme authority---in Garvey's ideal state the virtuous ruler would have no

close associations other than with his family and, free from the corrupting

influences that companionship might bring, would devote full attention to the

responsibilities of state.

|

|

a |