aa

|

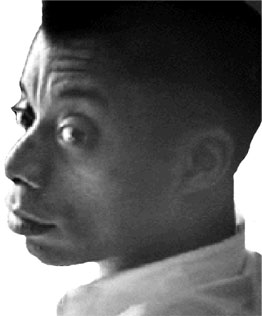

Marcus Garvey

Racial Education

Ethical and cultural instruction---the basis of virtue in

Aristotle's ideal state---was one of the basic goals of the UNIA from its

inception. Garvey believed in offering instruction both popularly and

institutionally, with the dual goals of reaching a wide audience and of

establishing educational facilities. The soapbox oratory, mass meetings, and

large conventions that characterized the Garvey movement were all directed at

instructing and organizing a large mass of people. Similarly, the dramatic

performances, elocution contests, debates, and concerts that UNIA members

participated in were forms not only of fund-raising and socializing, but of

racial education as well. When Garvey purchased Edelweiss Park in Kingston,

Jamaica, as a meeting center for the black community in the early 1930s, he

continued the practices established in New York and throughout the local UNIA

divisions---practices based on the nineteenth-century tradition of the

Chautauqua circuit, where people would gather locally for popular education and

enrichment combined with entertainment, often outdoors or beneath a tent. He

advertised Edelweiss Park as a "great educational centre" and a "centre of

people of intellect" in the pages of the New Jamaican.

Garvey's interest in founding educational facilities was also a

lifelong one. He attended courses at Birkbeck College in England before he

founded the UNIA in 1914, and one of the new organization's earliest goals was

the creation of an industrial training institute for black people in Jamaica

based on the Tuskegee model. Well before the turn of the century, the practical

education in skilled crafts that industrial training offered had become one of

the popular paths for artisans in their quest for self-culture. The 26 March

1915 Jamaican Daily Chronicle reported that Garvey listed the establishment of

"educational and industrial colleges for the further education and culture of

our boys and girls" as among the several benevolent goals of the UNIA. Garvey

received support in this goal from Booker T. Washington, who, on 17 September

1914, wrote to invite the UNIA leader to "come to Tuskegee and see for yourself

what we are striving to do," and promised again in April 1915 to help Garvey

achieve his local aims.

Garvey's interest in education based on the principles of

self-culture persisted after Washington's death in November 1915 and the

relocation of the headquarters of the movement in the United States in 1916.

UNIA meetings and programs continued to foster the ideal of self-improvement,

and as the association grew, auxiliaries were created with their own educational

standards for membership. These standards included examinations in the geography

of Africa, mathematics, reading, writing, and other subjects for commissioned

officers in the uniformed Universal African Legion; first aid and nutrition

classes for the members of the Black Cross Nurses; automobile repair and

operation instruction for the Universal African Motor Corps; and a curriculum of

elementary courses, including instruction in black history, economics, and

etiquette, for members of the Juvenile Divisions. In some areas, local Black

Cross Nurse auxiliaries also contracted with community hospitals and clinics to

provide members with more advanced practical training in nursing and maternity

care.

In February 1918 Garvey invited Columbia University president

Nicholas Murray Butler to address the members of the UNIA on the topic of

"Education and What It Means" and in April of the same year he and the other

officers appealed to Butler to contribute toward the purchase of a $200,000

building in Harlem for an organization headquarters, which they hoped would "be

the source from which we will train and educate our people to those essentials

that will make them a more cultured and better race."

|

|

a |