aa

|

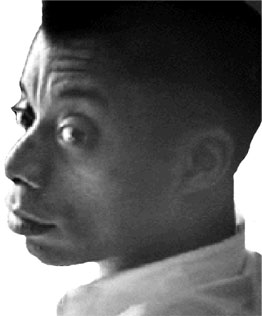

Marcus Garvey

Plato's Laws

Garvey borrowed the concept that the key function of law is the

maintenance of authority not only from Aristotle, but from Plato, whose Republic

and Laws presented a vision of an ideal state in which virtuous behavior is

encouraged through education, while conduct deemed corrupt is punished according

to a harsh system of penalties. Plato's penal code was in turn partially derived

from the Hammurabic code that preceded it. The crimes of embezzlement and

treason to the state through political factionalization, which Garvey suggested

should be punishable by death, were also crimes meriting capital punishment in

Plato's ideal state (Laws, 9.856) (however, Garvey's call for stoning as the

means of administering the death penalty is more likely derived from biblical

descriptions than from Plato). Plato recommended that all public officials be

subject to an audit and, should the audit reveal unjust self-aggrandizement, "be

branded with public disgrace for their yielding to corruption" (Laws,

6.761--762). Similarly, Plato wrote that "the servants of the nation are to

render their services without any taking of presents" and, if they should

disobey, be convicted and "die without ceremony" (Laws, 12.955). If, however,

leaders passed the state audit and were shown to have discharged their offices

honorably, they should, as Garvey's virtuous leader would, be pronounced worthy

of distinction and respect throughout the rest of their lives and be given an

elaborate public funeral at their deaths (Laws, 12.946--947). Just as Garvey

suggested that a child who identified a father's crime should be spared the

penalty of death, so Plato suggested that children who "forsake their fathers

corrupt ways, shall have an honourable name and good report, as those that have

done well and manfully in leaving evil for good" (Laws, 9.855).

Garvey's inclusion of kinship and property relations in

consideration of the organization of his ideal state also mirrored the teachings

of the Greek philosophers. He borrowed from Plato, who saw the state evolving

from the family into a more communal relation and who granted free women some

role in public life, in "universal education," and in the administration of the

state. Garvey also borrowed from Aristotle, who, more than Plato, preserved the

notion of the private household and the subordination of women as an integral

part of his ideal state. Garvey centered the private life of his ideal ruler in

a nuclear family and made the wife of the ruler a kind of chamberlain

accountable for her husband's financial dealings. Both Aristotle and Plato based

their ideal states on monogamous marriage and patriarchy, in which the household

of a citizen was compared to the larger hierarchy of the state, with a wife

subject to her husband as a subject is subordinate to a ruler. Garvey echoed

this model in his essay, wherein the wives of leaders are deemed "responsible

for their domestic households," regulated by law in the keeping of their

husbands' private and public accounts, and subject to capital punishment along

with their husbands for financial crimes committed during their husbands' tenure

in office. Garvey's recommendation that both the wife and husband should be

disgraced and put to death in cases of corruption in office mirrors not only the

family relations of the Greek state but archaic Mesopotamian codes governing

debt slavery, in which the wives or children of a male debtor could be enslaved

or put to death in payment for his financial failures.

|

|

a |