aa

|

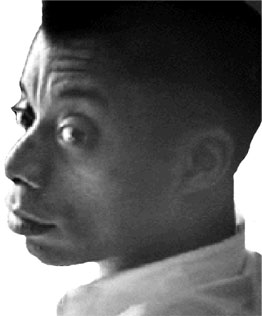

Marcus Garvey

African Fundamentalism

"African Fundamentalism" was Garvey's quasi-religious manifesto

of black racial pride and unity. It attained canonical status within a short

time after it was first published as a front-page editorial in the Negro World

of 6 June 1925. Written, like The Tragedy of White Injustice, while Garvey was

confined in the Atlanta penitentiary, the essay proclaims ideological

independence from white theories of history, makes concomitant claims of racial

superiority, and articulates major themes that recur throughout Garvey's other

writings and speeches. Chief among these are the ideas of racial

self-confidence, self-development, and success; international black allegiance

and solidarity; and the importance of acquiring a knowledge of ancient black

history.

Garvey's use of the term fundamentalism in the title reflects

this stress on the need for regaining a proud sense of selfhood by setting aside

modern racist labels of inferiority and reviving the basic, fundamental beliefs

in black aptitude and greatness that he saw exemplified in ancient African

civilization. At the same time, the term resonated with Garvey's long-standing

preoccupation with development of an original "Negro idealism." This notion was

essentially grounded in religion. "I don't think that anyone who gets up to

attack religion will get the sympathy of this house," Garvey declared in a

speech in 1929, "for the Universal Negro Improvement Association is

fundamentally a religious institution.

"African Fundamentalism" was written at the peak of the

fundamentalist revival that swept America following World War I. The revival was

expressed both as a theological doctrine and as a conservative neopolitical

movement. While the concerns of Christian fundamentalists focused on a

sociocultural return to a set of principles untainted by modern rationalism and

secularism, and while Populist fundamentalists called for the maintenance of an

older agrarian order that would belie the impact of industrialization and

urbanization---so Garvey's call heralded a recognition of the achievements of

Africans in the past and a return to the principles of black dignity and

self-rule, principles that had been denigrated under the impact of modern racial

oppression, slavery, and imperial colonization.

As in his sardonic use of the phrase "Vanity Fair," Garvey's

choice of the word fundamentalism reflects an intuitive understanding of the

types of associations people would apply to his use of the term. He employs

these associations in the context of the essay itself, wherein his references to

monkeys, caves, and the process of evolution inevitably call to mind the

opposing ideas of social Darwinism and the fundamentalist movement. The conflict

between these two philosophies peaked symbolically in the Scopes trial, which

got under way during the same summer "African Fundamentalism" was written. The

trial, which was held in Dayton, Tennessee, in July 1925, pitted prominent

attorneys William Jennings Bryan and Clarence Darrow against one another in a

much-publicized courtroom battle. At issue was the acceptance of the theory of

evolution and its place in the American school curriculum. Bryan argued for the

creationist viewpoint (a fundamentalist perspective associated with the agrarian

and southern sections of the United States and with the lower classes), while

Darrow represented the modern, humanist viewpoint (a secular perspective

associated with the urban and industrial areas of the North, with the growth of

the social sciences, and with the educated middle classes). Bryan's side in the

conflict prevailed, and teacher John T. Scopes was found guilty of breaking a

law passed by the Tennessee legislature in March 1925, prohibiting the teaching

of any doctrine denying the divine creation of mankind as taught from a literal

interpretation of the Bible.

In his essay, Garvey played on the social Darwinist issues that

were publicly highlighted by the Scopes trial and gave them an ironic twist. He

adopted elements of the evolutionary theory of the secularists and of the strong

nativist strain of the fundamentalists and utilized them both as premises to

support his own counterargument. He presented black people in northern Africa as

representatives of a higher form of life and culture than their white

counterparts in Europe. He thus reversed the popular contemporary claims of

white eugenicists, who applied evolutionary theory to the social milieu,

associating people of African heritage with the slow development of the apes and

offering their results as "proof' of white racial superiority. Similar reversals

of white-dictated beliefs and standards were reflected in Garvey's fervent

praise for the compelling beauty of black skin and African features; in his

championing of the worship of black images of the Virgin Mary, God, and Jesus

Christ in the place of white conceptions of the deity; and in his call for a

recognition of the heroic accomplishments of black people, such as Crispus

Attacks and Sojourner Truth, whose martyrdom, selflessness, and rebelliousness

qualified them for respect equal to that accorded white saints like Joan of Arc.

|

|

a |